Introduction

Suppose that we observe a quantitative response $Y$ and $p$ different predictors $X = X1, X2,…,Xp$. We assume that there is some relationship between them, which can be written in the very general form:

\[Y = f(X) + \epsilon\]- $f$ is some fixed but unknown function of $X$.

- $\epsilon$ is a random error term, which is independent of $X$ and has a mean of zero.

Estimate function

We create an estimate $\hat{f}$ that predicts $Y$: $\hat{Y} = \hat{f}(X)$. There will always be two errors elements:

\[E (Y - \hat{Y})^2 = [f(X) - \hat{f}(X)]^{2} + Var(\epsilon)\]Where:

- $E (Y - \hat{Y})^2$ is the average squared error of predictions.

- $[f(X) - \hat{f}(X)]^{2} $ is the reducible error. Our aim is to reduce this error.

- $Var(\epsilon)$ is the irreducible error, that cannot be predicted using $X$.

Predictions vs Inference

When focusing on predictions accuracy, we are not overly concern with the shape of $\hat{f}$, as long as it yields accurate predictions for $Y$: we treat it as a black box.

When focusing on inference, we want to understand the way that $Y$ is affected as $X$ changes, so we cannot treat $\hat{f}$ as a black box:

- Which predictors are associated with the response? Which ones are the most important?

- What is the relationship between the response and each predictor: positive or negative? Is there covariance?

- Can the relationship between $Y$ and each predictor be adequately summarized using a linear equation, or is the relationship more complicated?

Quality of Fit - Bias vs Variance

A good model accurately predicts the desired target value for new data. It will have:

- low bias: how well the model approximates the data.

- low variance: how stable the model is in response to new training examples.

We can link under- vs overfitting to bias and variance:

- the underfitting model does not capture the relevant relations between features and outputs: it suffers from high bias.

- the overfitting model captures the underlying noise in the training set, so changing the training set will lead to vastly different predictions: it suffers from high variance.

The figure below illustrates the range of predictions for a given input by a model trained with different datasets, depending on its bias and variance (source):

A more detailed article about the bias-variance tradeoff and how to identify under- and overfitting models is available on this blog.

Parametric vs Non-Parametric Methods

Parametric Models

- We make an assumption about the functional form, or shape, of $f$, the simplest of which is that it is linear.

- We fit the model to a training set. It finds the values of the function’s parameters that match $Y_{train}$ more closely.

Example for a linear model:

- $f(X) = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X_1 + \beta_2 X_2 + … + \beta_p X_p$.

- Find values of $\beta_0, …, \beta_p$ that minimizes the gaps between $\hat{Y}{train}$ and $Y{train}$.

The potential disadvantage of a parametric approach is that:

- the model we choose will usually not match the true unknown form of $f$. If the chosen model is too far from the true $f$, then our estimate will be poor (underfitting).

Simple parametric models will not work if the number of features is close to or higher than the number of observations (more details here). These cases will require a different approach, as explained in the section called Linear Model Selection & Regulatization.

Non-Parametric Models

Non-parametric methods do not make explicit assumptions about the functional form of $f$. Instead they seek an estimate of $f$ that gets as close to the data points as possible, without being too rough.

While non-parametric approaches avoid the issues of parametrics assumptions, they suffer from a major disadvantage: since they do not reduce the problem of estimating $f$ to a small number of parameters, a very large number of observations (far more than is typically needed for a parametric approach) is required in order to obtain an accurate estimate for $f$. It can also follow the noise too closely (overfitting).

Trade-off

- Linear models allow for relatively simple and interpretable inference, but may not yield as accurate predictions as some other approaches.

- Highly non-linear approaches may provide predictions that are more accurate, but this comes at the expense of less interpretability.

Categorical Predictors

Using categorical predictors requires some preparation. The most typical method is called one-hot encoding; it creates dummy boolean variables for all but one category: 1 if the observation has this category and 0 otherwise. The remaining category is called the baseline.

Model Assessment & Selection

A succesful model has low bias and low variance, which means it will accurately predict out-of-sample performance.

There are two main approaches to train and test a model:

- splitting the dataset in three subsets: one for training, one for validation and one for final testing.

- splitting the dataset in multiple train/test sets: cross-validation.

Train / Validation / Test Sets

We prepare the dataset for training the model:

- randomly shuffle data, in order to remove any bias that could stem from the original ordering of the dataset.

- split the dataset into training and testing subsets. Using a

random_stateensures the split is always the same. - a typical split is 80% of the observations for the training set and 20% for the test set.

This method risks overfitting the test set in case of multiple iterations (bleeding). A more robust method is to evaluate the model performance on a validation set during the entire iteration process, and to keep an holdout test set completely untouched. This holdout set will be used only at the very last stage of the process, to assess the accuracy of the final model on completely unseen data.

A typical split is 70% of the observations for the training set, 15% for the validation set and 15% for the holdout set. The drawback is that more data is required.

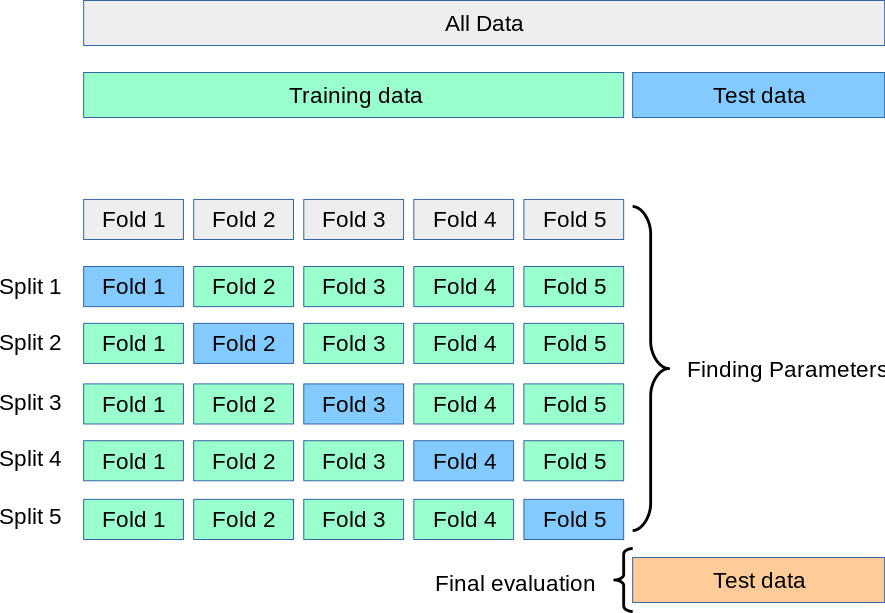

K-Fold Cross-Validation

Another method can be used to assess both bias and variance of a given model: K-fold cross-validation (k is usually set to 5 or 10).

- the dataset is divided in K subsets of equal size called “folds”.

- the model is trained K times, each run holding out a different fold as test set.

- the average testing score is used as an estimate of out-of-sample performance.

This method can be use to:

- assess the performance of a given model.

- compare the performance of several models.

Note: Leave One Out CV (LOOCV) is a specific case of cross-validation where k = n. It is more computationally expensive and source of higher variance: the n models all train on almost the same data so they are highly correlated with one another.

More information about Cross-Validation can be found here.

Bootstrapping

We can estimate the variability of an estimate across samples (i.e. quantify its standard deviation) without generating multiple samples via a process called bootstrapping: it consists of building many distinct data sets of the same size by repeatedly sampling observations with replacement from the original data set.

It is then possible to calculate the mean and standard error of the bootstrap estimates and use them to build a confidence interval for the parameter(s) of interest.

Note: this method can be used to calculate the standard error of coefficient estimates for linear regression, but without the underlying assumptions of linearity. It will therefore produce more accurate values when these assumptions do not hold.

Linear Models

Use cases

Linear models are great for inference. They help explain:

- if there is a linear relationship between variables.

- how strong is the relationship between variables.

- which variable(s) have a stronger impact on the outcome.

Relationships with Outcome

Coefficients t-statistics

Assuming that the errors are Gaussian, we can build a confidence interval for each coefficient of our model (in a way that is very similar to the confidence interval of the sample mean).

This allows us to test the null hypothesis that the true value of each coefficient is zero, i.e. that there is no relationship between a given variable and the outcome, given the estimated coefficient value and the resulting standard error.

We can calculate the p-value of the related t-statistic: how likely such a substantial association between the predictor and the response would be observed due to chance. Having a estimated value larger than the related standard error means that this probability is very small.

Model’s F-statistic

We can also test the null hypothesis that the true value of all coefficients is zero, i.e. that there is no relationship between the predictors and the outcome. This hypothesis can be assessed by the p-value of the model’s F-statistic.

Note: the squared t-statistic of each coefficient is the F-statistic of a model that omits that variable. So it reports the partial effect of adding that variable to the model.

Individual p-values vs Model p-value

Some p-values will be below the significance level by chance. This means that using individual t-statistics and associated p-values will probably lead to the incorrect conclusion that there is a relationship, especially if the number of variables is high.

The F-statistic, on the other hand, adjusts for the number of predictors. It means that it only 5% chance of Type-I error.

Variables Selection

If the p-value of the F-statistic shows that some of our model’s variables are related to the outcome, the next steps will be to identify which ones are important. There are a few classical methods to do it, if $p$ is the total number of predictors:

- Forward selection: start with the null model (no predictors). Fit $p$ simple linear models and keep the one with the lowest residual errors. Keep adding variables one by one until some condition is met.

- Backward selection: start with all predictors. Remove the one with the highest p-values. Keep removing variables until some condition is met (all remaining p-values under some threshold).

- Mixed selection: start with forward selection until the highest p-value crosses some threshold, then remove the predictor. Iterate until all p-values are below some threshold and adding any other predictors would lead to high p-values.

Note: Backward selection cannot be used if p>n, while forward selection can always be used. Forward selection is a greedy approach, and might include variables early that later become redundant. Mixed selection can remedy this.

Model Fit

The accuracy of a linear model is usually assessed using two related quantities:

- the residual squared error (RSE).

- the $R^2$ statistic.

Roughly speaking, the RSE is the average amount that the response will deviate from the true regression line. It is considered a measure of the lack of fit of the model.

$R^2$ is the proportion of variance in outcomes explained by the model. It is always between 0 and 1; the closer it is to 1, the better the fit. When the model only includes one variable, $R^2$ is equal to the squared correlation coefficient $r^2$.

Note: if the data is inherently noisy, or outcomes are influenced by unmeasured factors, $R^2$ might be very small.

Note: Measures of fit include Mallow’s Cp, Akaike information criterion (AIC), Bayesian information criterion (BIC), and adjusted R2.

Plotting residuals can help identifying patterns not captured by the model, like interactions between predictors.

Predictions

Predictions are associated with three categories of uncertainty:

- coefficients estimates.

- model bias due to distance of reality from linear assumptions.

- random errors due to noise.

These uncertainties can be quantified to provide:

- confidence intervals: average outcome given specific values of the predictors.

- prediction intervals: outcome for a given observation given specific values of the predictors.

Prediction intervals tend to be much wider than confidence intervals.

Mathematical Terms

The method of least squares minimizes the Residual Sum of Squares or RSS: the sum of all the error terms of the model.

\[RSS = \sum{(y_i - \hat{y_i})^2}\]The standard error associated with each coefficient are linked to the variance $\sigma^2$ of the error terms, which is assumed to be constant; it is not known in practice. $\sigma$ can be approximated by the Residual Standard Error or RSE:

\[RSE = \sqrt{\frac{RSS}{n - 2}}\]Relaxing Linear Assumptions

Assumptions

The two main assumptions of linear models describe the relationship between predictors and response.

- additive: the effect of changes in a predictor on the response is independent from the values of the others.

- linear: one unit change of a given predictor leads to a constant change in the response.

These highly restrictive assumptions that are often violated in practice, which requires more flexible models.

Interaction Terms

One possibility is to add interaction effects between variables, like this: $f(X) = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X_1 + \beta_2 X_2 + \beta_3 X_1 X_2$.

Note: The hierarchical principle states that if we include an interaction in a model (i.e. when the interaction term has a very small p-value), we should also include the main effects even if their individual p-values are not significant.

Polynomial Regression

Linear regression can introduce non-linear relationships by using polynomial terms, like this: $f(X) = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X_1 + \beta_2 X_1^2 + \beta_3 X_1^3$.

Splines

Piecewise polynomial regression involves fitting separate low-degree polynomials over different regions of X. The points where the coefficients change are called knots. Piecewise zero-degree polynomial are called step functions.

Adding more constraints to the fitted curve (i.e. reducing the degrees of freedom) lead to smoother fitting curves that are called splines. Their main drawback is that they have high variance at extreme values of X. A natural spline is a regression spline with additional boundary constraints: the natural function is required to be linear at the boundary (in the region where X is smaller than the smallest knot, or larger than the largest knot).

In practice, a spline regression requires to choose a polynomial degree, the number of knots and their percentile position.

A smoothing spline is a natural cubic spline with knots at every unique value of X. The smoothing parameter $\lambda$ controls the roughness of the smoothing spline.

Local Regression

Local regression uses only the k nearby training observations to fit some linear function to the new data; training observations closest to the new data are given a stronger weight. This approach can be very effective with time series: adapting a model to the most recently gathered data.

Generalized Additive Models

Generalized Additive Models (GAMs) extending standard linear models by allowing non-linear functions of each of the predictors.

$f(X) = \beta_0 + f_1(X_1) + f_2(X_2) + …$

We can fit non-linear functions to each predictor based on what relationship is has with the response.

Limitations of Linear Models

Residual plots are great tools to verify the assumptions of linear models. Problems arise in case of:

- non-linarity.

- correlation of error terms.

- non-constant variance of error terms (heteroscedasticity).

- outliers.

- high-leverage points.

- collinearity.

Non-Linearity

If the relationship between predictors and response is not linear, the model will fit the data poorly. Plotting residuals as a function of the predictions will show a strong pattern.

Correlation of Error Terms

The p-values and confidence intervals of linear coefficients are based on the assumptions that the error terms between observations are uncorrelated. This might not be the case with duplicate observations, or when the model does not account for enough variables.

In the case of time series, observations made at adjacent time points may be strongly correlated. Plotting residuals as a function of time will help spot tracking errors.

Non-Constant Variance of Error Terms

The standard errors, confidence intervals, and hypothesis tests associated with the linear model rely upon the assumption that the error terms have constant variance. It’s not always the case though: for instance, the variances of the error terms may increase with the value of the response.

Residual plots presenting a funnel shape indicate heteroscedasticity in the error terms. Transforming the response with a concave function like $log$ or $sqrt$ will help reduce it.

Outliers

An outlier is a point for which the response is far from the usual values. It can increase the RSE dramatically, leading to large confidence intervals and poor $R^2$. Outliers can either stem from an error in data collection or reflect deficiencies with the model, such as a missing predictor.

It can be difficult to decide how large a residual needs to be before we consider the point to be an outlier. Plotting studentized residuals (residuals divided by their estimated standard error) against predictions can help: observations whose studentized residuals are greater than 3 in absolute value are possible outliers.

High-Leverage Points

High-leverage points have unusual predictor values. They tend to have a sizable impact on the estimated regression line, so it is good to make sure they are valid observations.

The leverage statistic quantifies an observation’s leverage:

- individual values are always between 1/n and 1.

- the average leverage is always equal to (p + 1)/n.

Plotting studentized residuals as a function of leverage will help spot outliers with high-leverage.

Multicollinearity

Collinearity refers to the situation in which two or more predictor variables are correlated to one another. In that case, small variations in the data can lead to very different coefficient estimates with the same RSS. In other words, collinearity leads to a great deal of uncertainty in the coefficient estimates.

It means that the standard error of coefficient estimates is increased, leading to a smaller t-statistic and a reduced power of the hypothesis test. This means that we may fail to reject the null hypothesis.

The consequence is that collinearity reduces the probability of correctly identifying non-zero coefficients.

A correlation matrix of the predictors can highlight collinearity, but not multicollinearity (when three or more variables are correlated). Calculating the variance inflation factor (VIF) for each variable is a better way of assessing multicollinearity. It is calculated by measuring the fit of the regression of $X_j$ onto all of the other predictors:

\[\text{VIF}_j = \frac{1}{1 - R_{X_j | X_{-j}}^2}\]A large VIF (above 5 or 10) indicates strong collinearity. In that case, there are two main options:

- remove the problematic variables from the regression.

- combine the collinear variables into a single predictor (like by averaging the standardized values for each observation).

Linear Model Selection & Regularization

Limitations of Least Square fitting

Predictors vs Sample Size

The performance of least squares estimates is strongly impacted by the number of predictors vs sample size:

- assuming that the relationship between predictors and response is roughly linear, this method will have low bias.

- if n $\gg$ p: it will also have low variance and generalize well.

- if n $\approx$ p: it will have high variance, resulting in overfitting.

- if n < p: there is no longer a unique least squares coefficient estimate; variance is infinite.

By constraining or shrinking the estimated coefficients, we can often substantially reduce the variance at the cost of a negligible increase in bias. This can lead to substantial improvements in model accuracy.

Model Interpretability

Some or many of the variables used in a multiple regression model are in fact not associated with the response. Including such irrelevant variables leads to unnecessary complexity in the resulting model. By removing these variables—that is, by setting the corresponding coefficient estimates to zero—we can obtain a model that is more easily interpreted.

Alternative Methods

We will consider a few alternatives to using Least Squares fitting:

- Subset Selection: only keep the most relevant variables.

- Shrinkage or regularization: fit all predictors, but with coefficients shrunk toward zero.

- Dimension Reduction: project the predictors into a M-dimensional subspace, where M < p.

Subset Selection

Best Subset Selection

This algorithm requires a few steps:

- start with the null model (no predictors).

- for k = 1, …, p: fit all linear models with k variables. Keep the one with the smallest RSS.

- select the single best model using cross-validation to estimate out-of-sample performance.

Note: this approaches requires the training of roughly $2^p$ models and is therefore not applicable for but the smallest datasets.

Forward Selection

This algorithm requires a few steps:

- start with the null model (no predictors).

- for k = 0, …, p-1: fit p - k linear models that add one variable to the previous best model. Keep the one with the smallest RSS.

- select the single best model using cross-validation to estimate out-of-sample performance.

Note: This algorithm is greedy, so it might not capture the best possible combination of predictors.

Backward Selection

This algorithm requires a few steps:

- start with a model that uses all predictors.

- for k = p, …, 1: fit all k linear models that remove one variable to the previous best model. Keep the one with the smallest RSS.

- select the single best model using cross-validation to estimate out-of-sample performance.

Mixed Selection

This algorithm requires a few steps:

- start with forward selection until the highest p-value crosses some threshold, then remove the predictor.

- Iterate until all p-values are below some threshold and adding any other predictors would lead to high p-values.

Adjusted Training Error

An alternative to using cross-validation is to adjust the training error for the model size.

- $C_p$: adds a penalty proportional to the number of fitted predictors and the error variance.

- Akaike information criterion (AIC): maximum likelihood. Proportional to $C_p$ for least squares.

- Bayesian information criterion (BIC): similar to $C_p$, but penalizes large models more heavily.

- Adjusted $R^2$: penalizes models that include noise variables.

Shrinkage (Regularization)

Regularization aims to prevent overfitting by penalizing large weights when training the model: shrinking the coefficient estimates can significantly reduce their variance. It adds a regularization term to the loss function, with a regularization parameter called $\lambda$.

For both methods, increasing $\lambda$ decreases variance and increases bias (high values of $\lambda$ will lead to severely underestimated coefficients). See also this link for more information.

L1 Regularization - LASSO

- L1 regularization penalizes the absolute value of the weights.

- The resulting models are simple and interpretable, but cannot learn complex patterns.

- It can do feature selection: insignificant input features are assigned a weight of zero.

Note: lasso more or less shrinks all coefficients toward zero by a similar amount; sufficiently small coefficients are shrunken all the way to zero.

L2 Regularization - Ridge Regularization

Ridge regression works best in situations where the least squares estimates have high variance.

- L2 regularization penalizes the square of the weights.

- It forces the weights to be small but not zero.

- It is able to learn complex data patterns.

- Taking squares into account makes it sensititive to outliers.

Note: ridge regression is sensitive to scale, so it is best to standardize the predictors before using it.

Note: ridge regression more or less shrinks every dimension of the data by the same proportion.

Selecting the Tuning Parameter

To select the best value of the tuning parameter, we compute the cross-validation error for each value of a grid of possible values; we then re-fit using the model with all of the available observations and the selected value of $\lambda$.

Dimension Reduction

Dimension reduction methods transform the predictors before fitting a least square model, which is especially interesting when p > n. There are two main methods for achieving this:

- Principal Component Regression.

- Partial Least Squares.

Principal Component Regression

Principal components analysis (PCA) is a popular approach for deriving a low-dimensional set of features from a large set of variables. More precisely, it reduces the dimension of the n × p data matrix X. The actual number of principal components is typically chosen by cross-validation.

The first principal component vector defines the line that is as close as possible to the data. It is the linear combination (given by its principal component scores) of all predictors that explain the most variance in the predictors. Each successive principal component is the linear combination of all predictors, orthogonal (i.e. uncorrelated to) with the previous principal component, that explains the most of the remaining variance.

Note: It is best to standardize all predictors before running a PCR.

Note: PCR is not a feature selection method, because principal components are linear combinations of all original predictors.

Note: PCR and ridge regression are closely related.

Partial Least Squares

The PCR approach identifies linear combinations, or directions, that best represent the predictors X. These directions are identified in an unsupervised way, since the response Y is not used. Consequently, PCR suffers from a drawback: there is no guarantee that the directions that best explain the predictors will also be the best directions to use for predicting the response.

Unlike PCR, Partial Least Squares (PLS) identifies these new features in a supervised way: it attempts to find directions that help explain both the response and the predictors. It builds the first direction by taking a linear combination of the correlation coefficients between $Y$ and every $X_j$.

Note: PLS reduces bias compared to PCR but can also increase variance, so it often performs no better than PCR or ridge regression.

High-Dimensional Data

Data sets containing more features than observations are often referred to as high-dimensional. Classical approaches such as least squares linear regression are not appropriate in this setting, because the model is guarantee to overfit the training data: noise features may be assigned non-zero coefficients due to chance associations with the response on the training set. They increase the dimensionality of the problem without any potential upside in terms of improved test set error.

In these cases, the methods listed above will prove fruitful. the lasso in particular will help remove useless predictors.

Note: Even if many features are relevant, the variance incurred in fitting their coefficients may outweigh the reduction in bias that they bring.

Note: even when features selection leads to good predictions, the set of features actually selected is likely to be only one of many possible models that would perform just as well on unseen data, but with a different training set.

Generalized Additive Models

Features Selection

A few methods can be used to reduce the number of features and decrease the risks of overfitting:

- Remove features with low variance.

- Univariate selection: only keep features that correlate highly with the outcome feature.

- Regressive feature elimination: only keep the features that lead to the most accurate model in CV.

- LASSO: only keep features with non-null weigths.

- Tree-based features importance.

Linear Model Selection

Comparing Models

ANOVA can be used to compare two models.

Improving Models

General Strategy

- large sample size, few features: a flexible model would fit the data better; the large sample size will limit the overfitting.

- small sample size, large amount of features: a flexible model would probably overfit the training set.

- large variance of the error term: a flexible model would probably capture the noise and generalize poorly.

High Bias

Training error will also be high. Potential solutions:

- Add new features.

- Add more complexity by introducing polynomial features.

High Variance

Training error will be much lower than test error. Potential solutions:

- Increase training size.

- Reduce number of features, especially those with weak signal to noise ratio.

- Increase Regularization terms.

Non-Parametric Models

KNN Regression

K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) Regression looks for the K training observations closest to a given out-of-sample observation, then calculates the average of the K training responses. The model becomes smoother and less variable (i.e. more bias and less variance) as K increases.

When the number of predictors increases, an observation might have no nearby neighbors - the curse of dimentionality. In that case, KNN regression tends to fit poorly. As a general rule, parametric methods will tend to outperform non-parametric approaches when there is a small number of observations per predictor.

Hyperparameters Tuning

More information on hyperparameters tuning can be found here.

In the GridSearchCV technique, we define a range of values for every parameter we want to tune. The Grid Search will train models for each combination of values using K-fold CV, then outputs the compared performances.

This technique can become VERY resource-intensive for large datasets. In might be better to use RandomizedSearchCV in those instances.

Appendix - Further Reads

- Introduction to Statistical Learning (link to downlad the .pdf version)

-

Interpretable Machine Learning (github.io based e-book)

- bias / variance: what / impact / how to measure?

- loss function: how to define?

- cross-validation: when / purpose?

- R² vs adjusted-R²: when / good choice?

-

R² vs adjusted-R² on random noise

- feature importance: train or test set?

Links to double-check:

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bias%E2%80%93variance_tradeoff

- http://scott.fortmann-roe.com/docs/MeasuringError.html

- http://cs229.stanford.edu/materials/ML-advice.pdf